|

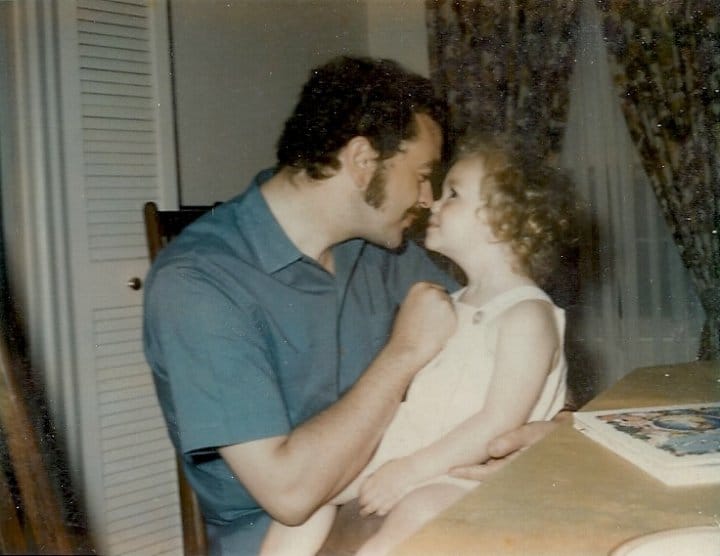

Four years ago today my brother died of a heroin overdose. Maybe not died - that could have happened days earlier. We're not clear on that. My brother lived in Colorado, my parents in Pennsylvania. I had moved down to Tennessee to be with T, so none of us could drop by Gunnar's place to check on him, even if we had been concerned. I found out only later that my brother hadn't answered his friends' calls for a couple days before he was found, the needle still in his belly. He didn't answer my call that day, four years ago, a few hours before his body was discovered. I didn't think anything of it. I was sure he was off somewhere in the summer sun with his dog, happy and laughing. Gunnar experienced joy just as fully and deeply as he did pain. Like me.

Before I allowed his friends in to clean out his apartment I spoke with the detective investigating his death, a kind man, who never once made us feel that Gunnar was just another dead junkie to him. I told him I had a very difficult question, but I needed him to be honest with me. I wasn't crying. I don't think my voice even broke as I asked him what the condition of my brother's body was when he was found. Would it be awful if his friends came to clean his apartment? I couldn't send these people, most of whom I knew, some of whom I loved, into that situation. No, the detective answered back. The fan in his bedroom had been on. It had been cool in there. They would be fine. Waiting for the detective to answer that question was not the worst moment of all the awful moments surrounding my brother's death. At that point I was riding a wave of dull, dumb numbness that even the term decomposition - never spoken aloud, but squatting like a poisonous toad in the back of my brain - couldn't quite pierce. No, the worst was the moment my father told me, over the phone, him in Pennsylvania, me in Tennessee, that my brother was dead. He said he didn't know how it had happened yet, the police officer who came to the door had just told him Gunnar had been found in his bed. I remember it took a bit for me to get that my dad was telling me my brother was gone. Irreversibly gone. Forever gone. T was standing before me, holding my arms, looking into my eyes. I whispered to him that Gunnar was dead and he helped slow my collapse to the floor. I hadn't quite understood the meaning of the word keening until that I heard the sounds that came from me then, an unholy mix of sobbing and screaming and the word "no" repeated over and over again. I cried until my voice was gone. I cried until my face was swollen. I don't know that I've ever really stopped crying. The tears are always there now, ready to spill over whether I'm happy or sad. I moved back into my parents' house after Gunnar's death, T joining me later. The grief I endured over the next months didn't lessen so much as mutate. I felt infested with it, like it had metastasized from my heart, creeping into my blood. My bones. The pain that had once been sharp, so sharp it made me double over, curl into myself with the force of it, turned into a relentless ache. I tried to alleviate it with therapy, with writing about my brother's death and the sorrow I was experiencing. I don't know that it helped. I didn't try to lose myself in drugs or booze or sex. When Gunnar died I was more emotionally stable than I'd ever been. But I still look back on that time with wonderment, amazed that his loss didn't destroy me. I knew that my brother's fate could have - should have, maybe - been my own. My end could have come at so many times, in so many ways. Suicide. Sex with a stranger who turned out to be a monster. An accident borne of self-destructive recklessness. Overdose. For decades I invited it all. But I dodged what Gunnar couldn't and I don't know why. Four years out from his death and I still sometimes wonder in my worst moments why I made it and Gunnar didn't. If I had died, would Gunnar have lived? Would he have gotten the help he looked for but never found, shocked sober and sane by my loss? Maybe part of the bottomless grief I feel is borne of survivor's guilt. Or maybe it's because I didn't try to save my brother, not really. I never visited him in the year between the admission of his heroin and crack use - just to me, not to our parents or his friends - and his death. I called him, checked to make sure he was still clean over a phone line from a thousand miles away, but I didn't get on a plane to go see him. My relationship with T was already a nightmare. I was already dying a little, losing who I was in order to be what he wanted. I believed that if I left T to go to Colorado he would make me pay for it, withdrawing his affection, what passed for his love. I was exhausted and confused and I chose T over my brother. I don't know how I live with this. I never got to tell Gunnar how brilliant and beautiful I thought he was. He knew I loved him, at least I hope he did, but I don't know if he ever knew how dazzled I was by him, by his charisma and humor, his intellect and generosity. That haunts me. Gunnar and I loved each other and battled each other in equal measure, two people too alike not to clash. But he was the one person I believed would be with me my entire life. My parents are in their 80s, in failing health. After they're gone I'll have no one. So I suppose my grief is not only for Gunnar, but for myself. For the years we should have ahead together, but don't. For the loneliness I'll soon face, and the longing for a family that no longer exists. People keep telling me, well-meaning people, people I love, that my grief will lessen. I don't believe them. My grief resides in a small, secret place tucked inside of me, where no one can go. I won't allow it to be made weak, or diminished. My grief will endure, burning cold and bright because I owe it to my brother to bear it.

23 Comments

Today, just now, my mom was admitted into hospice.

In Pennsylvania, at least when facilitated by and paid through Medicare, you're admitted into hospice when a physician has determined you have six months to live. In my mom's case, this is connected to an advancing case of COPD that now makes it difficult for her to go up and down the stairs without losing her breath. She has other health issues, including an aortic aneurysm that is slowly enlarging and can't be ameliorated through surgery due to her fragile condition. She's had two recent mini-strokes and she's in the early stages of dementia. So, I suppose this new categorization shouldn't have shocked me and my dad. But it did, of course. The nurse who arrived to talk to us about all this asked us a lot of questions about extraordinary measures to save my mom's life and if we've picked a funeral director and whether we want chaplain services. My dad and I numbly mumbled answers (no, we don't want any; no, but we're thinking cremation - it's starting to be a family tradition, after all, since my brother's death - no, we're not at all religious, but boy, it's times like these I wish we were). I found myself hating the nurse, who's name was Becky. Becky should be a cheerleader. Becky should be a capable mom, arranging car pools and swim lessons. Becky shouldn't be the woman who comes to tell you your mom is dying. I've been told that I need to face up now to this fast-approaching loss. It'll make it easier in the end, my friends say. But the truth is I'm already at the very edge of my ability to cope. These last couple of months I've felt so relentlessly hopeless that I'm not certain I can take one more blow right now, one more goddamn tragedy in the endless stream that the past few years have brought. And so I've been willfully, with a streak of pure, perfect stubbornness I inherited from my mom, disregarding this looming eventuality. Breakdown now or breakdown later? Later seems the better answer. I've been afraid for as long as I can remember of being alone. It's the fear at my center, the one that has motivated so much of what I've done in my life. And now here I am at 51, on the precipice of it. Unable to even date, if the truth be known, because my last relationship was so damaging I'm terrified I'll end up with the same type of man. My brother dead, my mom dying. My dad, 85 and walking around with kidney issues and an unhealed broken neck, getting a little bit more frail every day. No family here. No close friends, they've all scattered to the winds like starlings lifting off from a telephone line. No kids. I might as well be adrift in deep space. The future feels as cold and merciless as I imagine it to be. I'm so fucking scared. I'm so scared. And I don't know what to do. I'm less than six weeks away from climbing the tallest mountain in the Western Hemisphere, the thing I've spent the past 18 months directing so much of my energy, except what I've spent trying to care for my mom and dad, toward achieving. Getting to and up that mountain is the goal that's guided me through the the pain. The heartbreak and the loss. It's kept me sane and promised me a future less ordinary. If I give up now I don't know what will happen to me. But going up Aconcagua is a three-week trip. How can I leave my mom and dad for three weeks now? I'm trying so hard to be strong. I'm squirreled away in my room, writing, because it's the safest place I have. But I've got to stop crying and go hug my dad. After that, I don't know. I've been writing a long time about facing fear, about how it cracks open wide your life, and - to paraphrase Leonard Cohen - lets the light in. But I've just discovered it's one thing to face a fear of drowning by whitewater rafting, or of heights by paragliding off a mountain. It's another thing entirely to face a fear that you will not be strong enough to take care of your family when they need you most.

Almost a year ago exactly my father fractured his C1 and C2 vertebrae in a fall. He could have - should have, really - died. But he survived and after hours in our local hospital was transferred by ambulance 90 miles to a medical center with specialists more capable of handling his injury. While I was with him in the ER, T stayed with my mother. She's not really able anymore to spend much time alone. She's got emphysema, is on oxygen 24/7, is in almost constant pain from a distintegrating spine and is beginning to show signs of what I'm afraid is dementia. Once, not long after my brother's death, she was so confused that my father and I had to show her a photo of Gunnar and gently explain to her that her son was never coming home. "He died, Mom," I told her. "He's gone." I held her as she sobbed, thinking there was really not any way that I was going to survive the moment. It hurt too much. You always hear tell about how life is cruel, but until then I didn't understand just gleefully cruel it could be. The night my dad broke his neck my uncle and cousin came to stay with my mother, so T could be with me. We followed behind the ambulance bearing my father, the stars shining down on us with a brillance that only seems possible on the very coldest rural Pennsylvania nights. After Dad was tucked in to the ICU we checked into a motel. I remember I was afraid to go to sleep, terrified the phone would ring and a voice on the other end would tell me my father was dead. We were there three nights, the whole while my aunt and uncle watching over my mom at their house. Finally my father was stable enough to be transferred to a rehab facility in our town, where he stayed for two weeks. But I'd spent a lot of the time he was recovering in ICU numb with fear that I was going to lose him. The rest I'd pondered what I would have done without T. How could I have coped if I'd been without his quiet, steadfast support? What if, after spending all day at Dad's bedside in ICU, I would have had to go back to that motel and crawl into that cold bed, alone? I used to believe I would have broken apart. Maybe I would have. But I'm no longer the woman I once was. The pain of losing T - and my ability to negotiate that pain, as unlovely as the process has been - has honed me. I think it has sharpened my abilities to bear trauma and stress. If it doesn't kill you it makes you stronger. Eventually, that is, after it's first torn you apart, left you bloodied in a ditch by the side of the road. But if you rise up out of that place, the seams where you've stitched yourself together are more solid than you would have believed possible. Three days ago my father went to see his doctor. He wasn't feeling well. Before he could make it in he nearly collapsed in the parking lot. A creatinine blood test revealed he was in kidney failure. I took Dad to the ER, the same ER I'd taken him almost a year ago, after his fall, and waited four or five hours while they ran more tests. Although the ER physician believed his issues were only caused by dehydration, they admitted him. I was forced to leave mom alone. T, of course, is long gone, a memory I'm willing to become more faded, dull, like a Poloroid picture that never quite developed. My mother did fine. I did, too, on my own, taking care of my father. They discovered the next day that both of my Dad's kidneys were blocked by stones, which he's suffered from his whole life. I get them, too. They scheduled him for surgery, to implant stents to drain his kidneys and restore their function. Sometime that day, while Mom and I were visiting Dad in the hospital, our pug dog, Lola, injured herself. When we came home she was having trouble standing on her back legs. I spent yesterday getting Lola to the vet and Mom and me to the hospital, picking up Lola and taking her and my mother back home, making dinner and finally going back alone to the hospital tonight to spend time with my dad. It was stressful. It was exhausting. Mom and I got into a couple of arguments. I need to have so much more patience. Because she's scared, too, just like me. But it looks like Dad is going to be fine, though I just heard they're keeping him another night. We're hopeful Lola will mend, too. My Dad and I have had our issues, our blowups. But last night I was able to sit with him for a spell, reading aloud to him as the hospital quieted around us. I'll never forget it, that time. I'm grateful for it. I'm grateful, too, that I was able to handle everything, all of it, on my own. Not perfectly, or gracefully, or with as much good humor or equanimity as I would like. I want to do better. Unfortunately, I know I'll have the chance to try. But there is comfort in knowing that I didn't fail my parents. In knowing that I'm stronger than I once was - and less strong than I will someday be. I'm grateful for my mom and dad. They're old and difficult and broken in a way that can't ever heal by my brother's death. We fight. I'm not nearly as patient as I should be with them. I want to do better, but I haven't. And it kills me to see their health degrade, to see them sick and in pain. But they love me unquestionably in their imperfect way, the way I love them unquestionably in my imperfect way. We do the best we can, the three of us. And for that I'm grateful.

I'm grateful for my brother. I'm grateful that he lived, if I regret every day the way he died. I still sense him here, can nearly hear his great, booming voice and feel the way he he would wrap me in a hug, putting his whole big body and sprawling soul into it. Every once in while I still miss him so much it doubles me over. But how very, very lucky I am that I was Gunnar Shroyer's sister. I'm so grateful for that. I'm grateful for my friends. The ones who've come into my life after the end of my relationship with T, the ones I'd lost touch with have who re-entered it since and the ones who have been here forever, it seems, helping me navigate the crests and troughs of healing. This is one of the most difficult stretches of my life and it's because of you that I'm making it through. I hope you know how much I love you. For each of you I'm so very grateful. I'm grateful for the wild. For the mountains and forests and streams. For the paths that cross them, where I've felt a peace I've found nowhere else. Those three days last month I spent hiking the Appalachian Trail were some of the best of my life. How is possible that at 50 I've discovered this lust for the wild, this strong, steady need to wander it, to explore it, to pull it close it around me, like a lover or a gown of silk? I think this love, like all great loves, will take me somewhere I couldn't imagine when I first started to fall. I'm grateful for writing. It's hard. It hurts. But every once in a while, when I know that I've written something of beauty that might make someone feel not quite as alone as they did before they read it, I think there's a chance my life might just have meaning. I'm grateful for every single fucked up man I ever lowered myself to let inside my heart and head, because you've shown me what I don't want ever again. I'm grateful to every single man I've hurt, because you deserved better, and you've shown me who I don't want to be. I'm grateful for the sound of a train coming slow on the tracks, for good vodka and fast cars with stick shifts, for the candles I've lit in the cathedrals around the world for my brother, for hot sunshine and cool sheets, for the scents of lemongrass and lavender, and patchouli, too. I'm grateful for high heels, even though I shouldn't be, and great jazz, for the taste of dark chocolate speckled with sea salt, and the feel of champagne tickling my tongue. I'm grateful for sex, hot and fast or long and slow, and how my appreciation and need for it has only deepened with age. I'm grateful for the pleasure I'm discovering in working my body, in feeling it sweat and stretch, and that it's still healthy enough to do everything I ask of it. I'm grateful that I'm starting to believe I've still got a little bit of shine left in me. I'm grateful that I'm starting to believe I still got a great love ahead of me. I'm grateful that I'm starting to believe life still holds the magic of sweet surprise. I can't make this poetic. I can't make this beautiful. I probably can't even make this especially well-written. I'm so tired. It's a quarter after 11 on a Friday night. I've been crying pretty hard for a while now. The kind of crying that I can't really see through, that clogs my nose and makes my head hurt. The kind of crying that feels like it burns. Like the tears are so hot they scald the skin.

I guess I'm bottoming out. It's nowhere I haven't been but it's someplace I never wanted to return. It's been a long time since I felt this kind of isolation and pain - since back in the bad old days, back when anybody who knew me well probably wondered if I was going to make it. Would I see 25? Would I see 30? Would it be an overdose, a suicide, murdered by a lover? There was a time when I was a Class V tornado tearing through the lives of those around me, though I was as treacherous to myself as anyone else. Almost. I haven't been that girl, wild and reckless, driven nearly mad by an emotional pain that I could never name, in a decade, almost two. I'm still moody, probably always will be. I have a terrible temper. An Irish temper, actually. I've been named a spitfire only recently, and once upon a time, back when we met in Nashville, T called me "a handful." It wasn't so very long ago that a man in a bar took one admiring, appraising look at me and dubbed me "dangerous." It didn't displease me, exactly, though it was in front of a lover who ended our relationship soon after. I intimidated him, he told me. I've been told I glow and shine and pull people to me, almost like T pulled me to my feet and on to the dance floor without even asking that first night in Nashville. Those are good things. But like my brother, my poor lost brother, there is a price I pay for this bit of allure and it's the dark little speckle on my soul I carry, like a burn mark, maybe, or a cold spot. It's smaller than it's ever been. But it's still there and I'm feeling it more acutely than I have in years. I think I know what's going on. I think I know why I'm struggling so much, have been, for a couple of weeks. It's the comedown I always get when I return after a long run of travel - and this time I was out on the road, with just a few days home here and there, for almost two months. It's the goddamn holidays, too, which I dread this year almost with the intensity I dreaded writing my brother's eulogy. It's wrapping up my 60 page book proposal, as well, and the postpartum crash that comes inevitably after the conclusion of a big project. And it's the election, of course. Because I'm afraid, really afraid, of what's already happening to this country. I'm not easily frightened, at least not of men in dark alleys and low-lit parking lots. I've always walked where I wanted, when I wanted. I'm 5'9", I'm strong, and I move with assurance. It's protected me so far - or perhaps it's just been thanks to the same kind of fortune that safeguards drunks and small children - but I'm wondering if that blissful carelessness must now end. A friend of mine, a lover off and on through the years, messaged me the other night, concerned for my safety in the light of recent attacks on women. He was conflicted, but in the end advised me to get a gun and learn how to use it. But it's not really the possibility of physical violence that scares me. It's the vulnerability of my parents and me. We are so alone. I'm 50 years old, now partner-less, and doing my best to take care for them without any help at all, while working very long hours as an independent journalist. I make little money doing this, though I'm good at it. I am starting to see a little daylight; I've been getting better paying assignments and more of them. I hope to be making a decent living eventually from journalism, but in the meantime I supplement my income by working part-time seasonally in Penn State's Office of Admissions. My parents have outlived most of their savings, which was gutted by the market crash after 9/11. My dad has an unhealed fracture of his C1 and C2 vertebrae. My mother has COPD and is in severe pain from back issues; the two conditions have nearly rendered her bedridden. I take medication for various ailments, including diabetes, although I'm working hard to get in shape with the hope I can greatly alleviate these conditions. I see a therapist weekly. I believe if it weren't for her I might have been hospitalized. It's been a horrific few years. If it weren't for Medicare and Medicaid my parents and I wouldn't have health care. If it weren't for Social Security we might not have a place to live. I wonder, if the new administration has its way, how we're going to survive. And in the midst of all of this, two weeks ago, my therapist left the practice I use, one of the few that takes my insurance. She wasn't happy there, and told me during our last session that she had only stayed as long as she did so she could continue to counsel me. Laura understood me, saw me clearly and without judgment in a way few people ever have. I told her everything. Everything. I would walk into her office, terrified and sobbing, and she'd had me a tissue, patch up my psyche and send me on my way. Me thinking I just might be able to make until the next appointment. The last time I saw her she told that I give her faith in humanity. She actually said that. Faith in humanity. How do you respond to something like that? I just thanked her. Told her she might have saved my life. My new therapist is different. She wants me to fill out some kind of worksheet. Say affirming things to myself in the mirror. Write a goodbye letter to T, for God's sake. She says I'm in denial about the end of our relationship. I have trouble with that. The last thing in the world I want to be is some sad woman pining for a man who doesn't deserve her. It is possible to be in denial when I know that my life will be far, far better without him? I know we could never be together again. I don't know that I even still love him. I'm...processing. It would be so much goddamn easier to process if I could just be in another relationship. Although, I suppose the processing would stop, and that's the problem, isn't it? I hate being alone. I'm as terrible at it as I am terrified by it. I love love. And sex. And romance. I've been married once, engaged three times, and lived with I don't know how many men. But I'm trying to change my life, to heal that dark little speckle inside of me. And as Laura once said to me, "If you want a different result, why don't you try to do things differently?" And so that's what I'm doing, but the result is nights like this. Nights when I want to give up, but somehow manage to hold on, believing in the morning I'll feel just a little bit better. I'm getting stronger. At least physically. Emotionally...well, hell. If every day isn't a battle, it's a skirmish. But my body is changing. I feel it in the way I move, with an ease and pleasure I haven't experienced in years, since I stopped walking regularly. That almost daily, two mile stomp lost to depression and then inertia after I moved in with T. He hated me out in Knoxville at night, alone. But I'd long loved walking under the stars, did it in the quiet of my parents' neighborhood before I moved down south. Sometimes 10, 11 o'clock, I'd venture out, just me and the moon and the sound of the trees ticking in the breeze. The whole world felt like a secret then, whispered just to me.

But Knoxville's concrete didn't have any mysteries - at least none I cared to solve - and the walking fell away. I still don't walk at night, though now there is no one to tsk-tsk at me over its risks. To do so might remind me too much of T, of all the ways I frustrated and disappointed him, and besides, I don't need to - my training at Victory with Steve is returning fitness to me. I recently hiked five miles of local Appalachian forest, the trail taking me alongside mossy, chuckling streams and through glens where ancient mountain laurel loomed overhead, twining together, dense and fearsome. Graceful snakes slithered here and there, peeking out from under slender ferns, while butterflies gamboled overhead. And not one muscle in my body twinged. Nothing ached that day, or the one after, but my eyes, tender from crying, and fragile heart. On Tuesday I begin a two-week ramble through West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. We'll soon see exactly how much my body has evolved under Steve's guidance. I'll be rock climbing, paddle boarding and zip lining with Adventures on the Gorge in the New River Gorge area of West Virginia, a place I adore, that I've to returned to over and over again. It was where I discovered my love of adventure sports, and where I nearly drowned my first time white water rafting, when I was swept out of and then under the boat in a Class V rapid on the New River. Since that day my response to any body of water bigger than than a swimming pool has ranged from mild unease to outright terror, depending on its tranquility. I honestly have no idea how I'm going to cope on the two-day paddle we're taking down the Gauley River, the New's angrier, more brutal sister. One of the world's most violent waterways during dam release season, as it is now, the Gauley's been dubbed by river rats the Beast of the East. I am taking this trip because it is no longer only water which frightens me. It's the fear of living out the rest of my life never feeling again the way I did with T. Of never loving again, and being loved. It's the fear of losing my parents, the last of my family. Sometimes I wonder, daring myself to ponder the inconceivable, how long I have left with them. I live with them. What will happen to me when they're gone? How will I endure their loss? How will I survive adding it to the collection of mean little tragedies I'm too quickly amassing? There is only me left to pack up the house, to get it ready to turn over to the bank. When I try to think about doing that alone, my mind skitters to a stop. I think it's to prevent me from going mad. I'm taking this trip because I'm already drowning. I'm taking this trip because there is no one left to save me but me. I'm taking this trip because I believe it will help return a small, precious part of myself I lost, or, more precisely, abandoned these last few years. This trip is what I believe they call in rafting a self-rescue, the first of many I'll attempt. T famously rafted the Gauley once, during his long-ago grad school days. He had a couple posters of the river pinned up in our kitchen in Knoxville. We had the opportunity to tackle it together a few years ago, when two spots opened up on a rafting trip while we were visiting the area. We didn't do it. It would be too exhausting we said, to raft for hours and then drive home to Tennessee. And T told me - as he had told me many times before that day and would tell me many times after - that he worried about me on the Gauley. "It's big water, baby girl," he said. "It's dangerous." I told him that I needed to raft it, that I wanted to get over my fear. But I tucked his concern away inside me, thrilled and touched that he loved me so much he was afraid for my safety, each time we discussed the Gauley growing a bit more at ease with the idea that rafting it was a challenge I shouldn't face - much like skydiving. A few birthdays ago, when we were still in Knoxville, T had given me a certificate to parachute out of a plane as a present. He'd done it once upon a time, and he knew that I wanted to try it, too. When I opened the card holding the certificate he said, "Now, I'm not really comfortable with this. I'm not sure I want you doing it." And again I thrilled to hear the love, the apprehension in his voice. And somehow that skydiving trip never quite materialized. I don't really know what happened to me in those years with T, why my nerve increasingly failed me, why I began to believe myself weak, incapable. The answer isn't as simple as his coddling concern for me, which, though it rankled a bit, also made me feel protected. Cherished. But I am no longer willing to live my life an eroded version of the woman I used to be. In West Virginia, I'll be rafting some of the nastiest white water in the world. In Delaware, I'll be skydiving. And I'll have stepped a bit further down the path leading to Kilimanjaro and Aconcagua. They're still waiting for me, my mountains, quietly, with terrible patience. This is a story I've never told. This is the story of how, a little over two years ago, my brother died of a heroin overdose. I've hidden the truth from most people about Gunnar's death - even his friends, even our extended family - at the request of my parents. But I'm not ashamed of how he died, I never have been, and I think we dishonor him by hiding behind half-facts like "His heart failed." Yes, Gunnar's heart failed. His big, beautiful heart - strong, if never wise - failed because a few days after his college graduation he injected a dose of heroin into a vein in his belly. And it killed him. And he laid there, in his bed, for we're not sure how long. Perhaps a day. Perhaps - more likely - as many as three. While his cell phone rang and rang and rang, his hordes of friends wondering where he'd gotten to, and me and my parents thinking he was still alive. Thinking life would go on like it always had. Thinking we had time, still, to be a family instead of the weary, worn little band of survivors we've become.

About a year before he died my brother called me one night. I was living in Knoxville with T, had been for about three months. Gunnar told me that he'd been shooting heroin, been smoking crack. But he was several months clean. He was seeing an addiction counselor, a therapist, a nutritionist. He was working out; the gym was his new addiction. Not, I think, that he was ever precisely addicted to heroin. He wasn't a longtime user...it hadn't yet eaten away at all that was good in him. He was, at 42, entering his last year at the University of Colorado and maintaining a high G.P.A. as a philosophy major. He was, not to overstate it, beloved by his professors and fellow students. So many of them called and wrote us after his death. They sobbed when they talked to us, even his advisor. Gunnar was the single most magnetic human being I've ever met. I once called my brother the only person I knew who was a celebrity without being famous. He had hundreds of friends - and not just social media friends, but people he'd met over the years and drawn into his always-widening army of cohorts and admirers. Many of them modern-day hippies like him, whose best days were the ones spent inside a venue, at a Dead or Widespread Panic show. Everyone who knew him has a story. Rich, a friend to both my brother and me, talks about the time he casually mentioned to Gunnar that he liked his coat. My brother literally gave it to him off his back. "No, Richie, you have it," he'd insisted when Rich had objected. "Please, I want you to have it." Gunnar was equally generous with me, hitchhiking from Colorado to Oklahoma to help pack a moving truck and whisk me away from a toxic boyfriend. I was in the Memphis airport once with that same boyfriend, in a long line of travelers stranded by a storm at Christmastime, when I mentioned that I hoped Gunnar, at least, had made it home. "Gunnar??!!" hollered a girl in line behind me. "Did you say GUNNAR?? Do you know Gunnar??" After I nodded, told her yep, he was my brother, the little group around her cheered. Stranded at the damned Memphis airport at Christmas and there's a half-dozen people who know Gunnar. Do you know that two years after his death one of his friends is still making buttons with his picture on them, spreading them far and wide so my brother can still go to shows and travel the world? But Gunnar had something inky-black and hungry tucked inside of him, a cruel, sharp-toothed little beast that ate, ate, ate away at him, gnawing at any contentment he found, any peace. He hurt. I know it, because I recognized it. It was the same hurt I've felt within myself, only Gunnar had it in greater measure. I suspect that's why I'm still alive and he's dead. The worst part of it for me, the saddest, most terrible thing of all, is that he fought so hard to heal himself. So very hard. But he didn't quite make it. That night that Gunnar told me he'd been using heroin I didn't get angry. I think mostly I was just...dazed. I remember parts of my face feeling numb, my lips and fingertips going cold. I'm sure I said the most supportive things I could. After I finally hung up I went to T, crawled into bed beside him. "My brother," I said, "is going to die. He's clean now, but he'll relapse and overdose or get sent to prison. And then my parents will die. I'm going to lose them all. And then I'll be alone." T didn't say what I needed to hear. "I'm your family now, baby girl," he didn't say. "You'll never be alone, " he didn't say. He was probably even then wondering what he'd gotten himself into. As ferverishly as I loved him, a part of me was, too. I was wondering what I was doing with a man who often seemed as if encased in glass, under a bell jar. Unreachable. I didn't go out to Colorado to see my brother, to support him in his quest to keep sober. I was so overwhelmed, so depressed, my life in such upheaval after leaving my friends and family and moving down South to be with T. I couldn't muster the will or the energy necessary to make that trip. I don't kid myself that I would have saved him. That a year later he wouldn't have died, alone in his room. But he would have, at least, known how very, very much I loved him. Do you have a story about my brother? Please share it in the comments below, or if privacy is necessary, use the link above to email me. I'd really like to hear it. Last week, the day after my 50th birthday, I went to see my friend Shaie speak at the BuxMont Unitarian Universalist church in Warrington, outside of Philly. I occasionally attend services when I'm traveling, like the achingly beautiful mass given in Irish I witnessed on St. Paddy's Day in my beloved Dingle, Ireland a couple years back. But the habit is more about honoring and exploring the local culture than anything else. I'm not at all religious, though I guess you could call me spiritual. I'm uncertain of what comes next after this life, but I believe, or at least I very much want to, that something does. I've lost too many people I loved too much in the past few years to long consider any other possibility.

Though I attended the Unitarian service simply to support my friend, the sermon nonetheless worked it's way into me. Shaie, who is currently seeking her master's degree in divinity at Vanderbilt, spoke in her soft, sweet voice about the times in life, as she described, "that feel simultaneously empty and full, containing both endings and beginnings, moving the experience of life from what is known to what is new." She titled her sermon "The Blank Rune," after the stone in the ancient set of divinatory symbols that represents contact with true destiny, which may hold our highest good and yet brings to the surface our deepest fears. This space between that Shaie spoke of, where all is uncertain, filled with equal parts panic and potential, is where I live now. My past life, with a love I thought would last forever, with a younger brother I thought would live forever - Gunnar always seemed simply too vital, too big and filled with energy to ever die - and with healthy parents who could tend to themselves, is over. My new life, with its quest to ascend Kilimanjaro and Aconcagua next year, has barely begun. There is little I know with any sureness. Instead, there are only questions. Will I be able to make my body, mind and spirit strong enough to climb Kili, let alone the nearly 23,000-foot behemoth that is Aconcagua? Will I find the support from sponsors I need to make these trips happen? Will I have it within me to write a book about it all? Will I have it within me to care for my mom and dad with the compassion and diligence they deserve? Will I find great love again? And will I finally, finally make of my life something I can be proud? I have underachieved my entire adulthood, veering close to big, traditional success upon occasion, like the time I was one of a half-dozen women under consideration for the sidekick position on mega-star Mancow's syndicated radio show. But I never quite made it, always distracted by fallout from my chaotic life, or the next novelty to catch my easily unfocused attention. Often a man. Often a man broken and unworthy. The drug addict. The rage-aholic. The commitment-phobe incapable of intimacy. I used to joke that, given my choices in previous companions, my next lover would be a serial killer. It's not a joke I make anymore. I'm leaving these loves, and whatever emptiness within them that called to the hole in my soul, forever behind. No matter if its a place of healing, the space between is uncomfortable - it often hurts like hell, actually. It's terrifying to have no real idea what the future holds, only plans and intentions, dreams and desires. Living in the space between requires faith, a faith I find myself struggling to capture. It's like stepping off a precipice, trusting you will float rather than fall. But trust is really the only option, because when you start to fret about the future, to worry it, like rosary beads between the alabaster fingertips of an ancient cleric, you stop living. Trepidation sets in. Dread. And before you know it, you are immobilized. You become one of those people beaten by life, unsatisfied, unhappy, but incapable of reaching for better. More than anything I fear this surrender. So I'm trying to trust in the process, as Shaie suggested in her lovely sermon. To breath deeply and exist in the still, small moments - as yet rare and all the more precious for that paucity - when I am able to let go of doubt. I've set my goals and I'm working toward them. I will work toward them with more diligence, passion and focus than I've ever worked toward anything in my life. That's really all I can do, anyway. Work hard. Trust big. Trust that there is beauty and love and adventure and joy, too - real joy - ahead. Trust that all this pain and fear will one day dissipate, leaving just a distant, disquieting recollection, an ashy smudge of a memory of the time when I thought I just might not make it. This is the beginning. This is how it starts, with a whimper, not a bang. My name is Jill Gleeson and in 11 days I will turn 50 years old. It's something I may find difficult to discuss with any semblance of wit or intelligence - though I will do my best as we go forward - because basically I have no clue how in the hell I got to be so old. I was 24, like, the day before yesterday. And it was fun.

|

Jill GleesonJill Gleeson is a journalist based in the hills of western Pennsylvania. She is a current contributor to The Pioneer Woman, Country Living, Group Travel Leader, Select Traveler, Going on Faith, Wander With Wonder, Enchanted Living and State College Magazine, where her column, Rebooted, is featured monthly. Other clients have included Email me!

Archives

May 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed