|

We went easy on our trek through the High Atlas. Slowly and carefully. I was climbing with someone who'd never done anything of the sort and it was enormously difficult for them, not the least because they were terrified of heights. I didn’t know that until we were well on the mule path, when we discovered how steep the drop from it was. Maybe we should have asked Ahmed, our guide, to take us back, but I was already gone, blissful and selfish. Stoned on the discovery that I still belong in the mountains. Or maybe it’s more that I belong to them.

The joy that I felt as the land fell away beside the path, opening up the view to the Berber villages thousands of feet below, was undistilled and overwhelming. It was almost impossible to rein myself in - I wanted to feel my heart thrum and my breath hasten and the muscles in my legs grow hard and unyielding as they struggled to carry me onward. I tried to slacken my pace, but I often found myself so far ahead of the others I had to stop and wait for them. I’d stiffen if I sat, so I remained standing, looking at Morocco spilling out beneath me. It was my first time in the mountains since I failed to summit Aconcagua. I don’t know that I can count the slog up Little Malene in Greenland a couple weeks back, as difficult as it was. I never felt immersed in that landscape the way I did in the High Atlas range. We didn’t venture deep into the outback in frozen Greenland, though the climb was harder, with a sharper elevation gain. The ascent in Morocco was initially gradual. The toughest part for anyone with acrophobia, like the other trekker I was with, was the slender path, and the fear of the long fall if you stepped off of it. Maybe I burned through any fear of falling at the beginning of the trek. I think the greatest concern anyone has for me - at least I’ve been told this, often with as much consternation as love - is that I’m reckless. That I take too many chances, don’t consider the consequences. I suppose it’s true; I’ve been trying to live a more careful life. I don’t know that I’m any good at it. Because after Ahmed gleefully scrambled a few feet up what was more a wall and less a hill, returning to earth dusting his hands with a grin, I challenged him to take me up it. He told me it was dangerous, that the path up wasn’t even a mule trail. It was only for mountain goats and mountain guides, specifically those who had grown up in the High Atlas, like him. But I pushed and Ahmed eventually gave in and up we went. I was fine ascending, even as we climbed hand over feet, 10 feet, 20 feet, 30 feet and even higher. I think I was at one point four or five stories up, totally unsecured, with no one belaying me. The precariousness of my situation didn’t hit me until we needed to start moving across the face of the incline. We left the path, which wound higher, and it made me feel every step was insecure. If I’d fallen I would have bounced until I hit the road that was far enough beneath me I’d have been killed, or at least badly broken. It crossed my mind that I could become a very sad and even more stupid cautionary story about a woman who pushed it too far once too often. After I lost my nerve I spent some time sort of shuffling on my ass across the dirt, stone and scrub, until I felt more stable and could stand, a bit wobbly and ever so carefully, again. In another 10 minutes we'd picked our way off the hill, onto the road. We continued on, methodically trekking toward the Tizi Mzzik Pass, 3,000 feet higher and six miles away. I didn’t feel any elevation sickness along the way, although we eventually reached more than 8,000 feet in elevation. I’m not sure if I should be heartened by that, when it was acute mountain sickness that got me booted off Aconcagua. But I am. I haven’t trained, not once, since coming down from Aconcagua in February, but I felt so strong during the trek. The last section was very steep, a merciless switchback that I climbed slowly, but without getting winded. My steps were sure and I worked my walking sticks well, in proper rhythm with my stride, even as we raced against the encroaching darkness to make it off the mountainside before full night fell. It felt right, my being up there, right the way it is when you fall in love, or the perfect song comes on as you’re driving fast down a back road in summertime, the sun bright and the wind soft. It felt, I suppose, like coming home.

8 Comments

It's been one week to the day since I was banished from Aconcagua, summarily sent down from it, like an inept baseball player kicked from the major league to the minors. I haven't really had time to process what happened, or to understand what it ultimately means to my life, other than to label it a failure. After all, I wanted something - to reach the tippy-top of the highest mountain outside of Asia - and it didn't happen. I didn't summit Aconcagua. Hell, I didn't even get close. I didn't even make it past the approach camp, a victim of mountain sickness, according the physician who fretted over my vitals before announcing, with great gentleness, that I was in jeopardy and would continue to be until I descended.

That's failure and I will always label it as such, which seems to confound and annoy just about everyone around me. I've heard this week that I can't be a failure because I tried to accomplish something most wouldn't, because it was my body that gave out and not my will, because this kind of setback is just a part of mountaineering and because, simply, I didn't die. I understand the reasoning behind all that, and am grateful for the kindness that led my friends and fans to share these thoughts with me. I just don't agree. I had a goal. I didn't achieve that goal. I failed. Why are we so afraid of failure in this country? Why do we twist and turn the situation in which we failed upside down and all around, spinning it like a kid appraising a package on Christmas morning, just so we can call it anything but what it is? The way I see it - and I'm quoting President Obama here - "If you are living life to the fullest, you will fail." As Oprah Winfrey says, "If you're constantly raising the bar, if you're constantly pushing yourself, higher, higher, higher, the law of averages, not to mention the myth of Icarus, predicts you will at some point fall." And that's okay. Because the alternative, to not even try, is far worse for me. I don't mean to sound like Dr. Phil or Tony Robbins or Brene Brown, as much as I love her, or Yogi Bear or the Dalai Lama himself. I don't feel comfortable making pronouncements about how anyone else should live. But for me, passion, adventure, excitement, which I now get mostly from pushing myself damn hard and then harder and harder still, make life bearable. If I didn't try - be it anything from climbing a mountain to moving to a country where I know no one on not more than a whim - there's a chance I might go mad. Or at least back to the self-destructive ways I once utilized to get my fix of chaos, the metaphorical equivalents of driving too fast in a big-motored car down a dark highway, fucked up on mania and dope and lust, the thick fingers of the dangerous man perched beside me in the passenger seat creeping up my naked thigh. Or, actually, the literal equivalents, too. I'm not a great white shark - I don't need to be in constant motion to survive, although I have some former lovers I expect would disagree on both counts. But I do need something to work toward. Looking ahead keeps me sane. I need to challenge myself, the more viscerally the better. That little divot I have inside my soul, the place damaged, if not quite broken, by what I've never discovered, is filled for a time when I do. Risking it all, or as much of it as I can, soothes me. My plan to climb Aconcagua and Kilimanjaro, which I announced a little more than 18 months ago, was undoubtedly an outgrowth of this need. But more crucially, it was an attempt to save myself. I was in danger back then, more danger than I ever faced on that mountain. The loss of my brother to a heroin overdose, an event that still lurks beneath every moment of every day, ready to rise up and throttle me with grief; the decline of my parents, with whom I live, rendered in cruel close-up and most recently encompassing my mother's dementia diagnosis; and the final blow that nearly destroyed me, the end of a relationship filled with enough love and toxicity it's taken me nearly two years to emerge from it fully, like a freed prisoner creeping slowly from a basement cell - these events and more, piled fast one atop another, made me question whether living was a worthwhile effort. I questioned it a lot back then. I needed to find a way to quiet all that tragedy, to hush it, so I could hear the sounds of life again, find the path back to it. Embarking on a quest so massive it was ridiculous, like scaling two of the Seven Summits within a year, seemed the way to do it. I hoped along the way it would turn me into someone I wasn't - a woman not vanquished by pain, but one heroic, strong, invincible. A warrior, inside and out. A woman who ascends big damn mountains. And I failed. I came down from Aconcagua two days after I went up it. I suppose I should be humiliated. But I'm not. Because I have felt a shift within me. Maybe I'm simply riding high with a giddiness born from emerging off Aconcagua with fingers, toes and nose intact (I was never really afraid of the mountain killing me, but not so the idea of of losing bits and pieces of myself to frostbite). Maybe I'm simply grateful to be released from the exhaustion I felt nearly as soon as I started the first trek. Pervasive and absolute, it destroyed my resolve, turning what was supposed to be an easy five-mile hike into a grim battle marked by my tortured, runaway breath and staggering feet. The next day, when I was forced to ask one of my expedition's guides to take me back to camp less than halfway through our trek, was worse. I didn't understand why, when I'd trained so hard for Aconcagua, I felt a fatigue on its lower trails that nearly trumped what I endured during my eight-hour push to Kilimanjaro's 19,341-foot-high summit. Would Aconcagua have killed me if I’d have bullied and begged, stamped my feet and cried, somehow convincing the physician - an improbably beautiful and compassionate Argentinean woman who looked like a grittier version of Salma Hayek - to let me continue the ascent? I don’t know. I don’t know how sick I really was, only that over the course of two nights my blood pressure had risen from 140 over 90 to 165 over 110. My heart rate increased to 130 and my oxygen saturation fell to 84. Not awful numbers, but what concerned my glamorous doctor was that my vitals were worsening instead of getting better. I wasn’t acclimatizing to the altitude. It hurts that I failed to summit Aconcagua, hurts like a pinch cruel enough to leave a bruise, a result common to the collision of dreams and reality. But I'm grateful for the experience I had in Argentina. Right now, as I sit here typing this, I feel something that could be called hope and I think that brutal bitch of a mountain that I love and fear in equal measure returned it to me. Will I return to her? I don't know. But my hunger for her summit, a growling yearning very different than the pain that consumed me 18 months ago, continues. Today, just now, my mom was admitted into hospice.

In Pennsylvania, at least when facilitated by and paid through Medicare, you're admitted into hospice when a physician has determined you have six months to live. In my mom's case, this is connected to an advancing case of COPD that now makes it difficult for her to go up and down the stairs without losing her breath. She has other health issues, including an aortic aneurysm that is slowly enlarging and can't be ameliorated through surgery due to her fragile condition. She's had two recent mini-strokes and she's in the early stages of dementia. So, I suppose this new categorization shouldn't have shocked me and my dad. But it did, of course. The nurse who arrived to talk to us about all this asked us a lot of questions about extraordinary measures to save my mom's life and if we've picked a funeral director and whether we want chaplain services. My dad and I numbly mumbled answers (no, we don't want any; no, but we're thinking cremation - it's starting to be a family tradition, after all, since my brother's death - no, we're not at all religious, but boy, it's times like these I wish we were). I found myself hating the nurse, who's name was Becky. Becky should be a cheerleader. Becky should be a capable mom, arranging car pools and swim lessons. Becky shouldn't be the woman who comes to tell you your mom is dying. I've been told that I need to face up now to this fast-approaching loss. It'll make it easier in the end, my friends say. But the truth is I'm already at the very edge of my ability to cope. These last couple of months I've felt so relentlessly hopeless that I'm not certain I can take one more blow right now, one more goddamn tragedy in the endless stream that the past few years have brought. And so I've been willfully, with a streak of pure, perfect stubbornness I inherited from my mom, disregarding this looming eventuality. Breakdown now or breakdown later? Later seems the better answer. I've been afraid for as long as I can remember of being alone. It's the fear at my center, the one that has motivated so much of what I've done in my life. And now here I am at 51, on the precipice of it. Unable to even date, if the truth be known, because my last relationship was so damaging I'm terrified I'll end up with the same type of man. My brother dead, my mom dying. My dad, 85 and walking around with kidney issues and an unhealed broken neck, getting a little bit more frail every day. No family here. No close friends, they've all scattered to the winds like starlings lifting off from a telephone line. No kids. I might as well be adrift in deep space. The future feels as cold and merciless as I imagine it to be. I'm so fucking scared. I'm so scared. And I don't know what to do. I'm less than six weeks away from climbing the tallest mountain in the Western Hemisphere, the thing I've spent the past 18 months directing so much of my energy, except what I've spent trying to care for my mom and dad, toward achieving. Getting to and up that mountain is the goal that's guided me through the the pain. The heartbreak and the loss. It's kept me sane and promised me a future less ordinary. If I give up now I don't know what will happen to me. But going up Aconcagua is a three-week trip. How can I leave my mom and dad for three weeks now? I'm trying so hard to be strong. I'm squirreled away in my room, writing, because it's the safest place I have. But I've got to stop crying and go hug my dad. After that, I don't know. Maybe he's just what I need, when I need it, this feral man I'm about to take off across the South with, just the two of us and his guitar in a throwback maroon van, shiny with chrome, smelling of me - patchouli and lemongrass - and him - clean sweat and sweet weed - and the musky, satisfied scent our bodies create together. It wasn't supposed to be this way. I didn't expect to see him after Nashville and that weekend I can't quite remember that left me with a broken foot and a lost voice and shining eyes and a pretty-near healed heart.

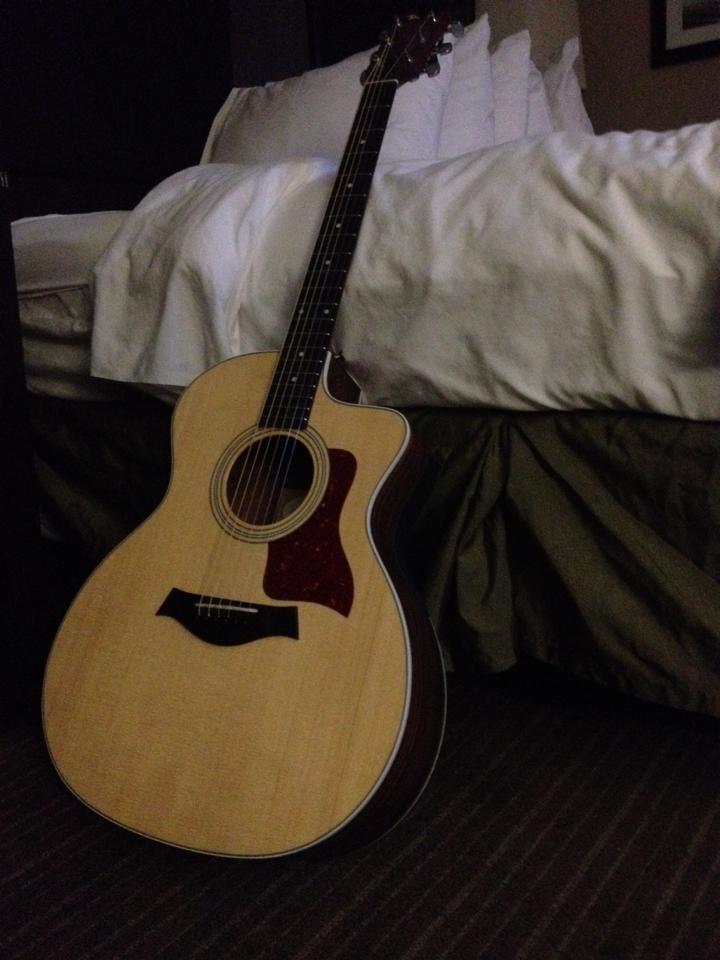

But CC called me after I got home and I answered and he hasn't stopped calling and I haven't stopped answering. I texted him a few weeks after Nashville late one night, wrote him that I was thinking of how we had lain naked and smooth together under that white, soft sheet. We should hook up, he replied. New Year's. We met in the middle, exactly halfway between us, in Charleston, West Virginia, and he wasn't irritated I was hours late. I could hear his guitar as I walked down the motel hallway and when I opened the door he smiled. We spent most of those three days in bed. He's as hungry as I am. We've been tormenting each other for a week now, as we get closer to our next tryst. Whispering what we want in late night phone calls, swearing that we aren't touching our own bodies, that we're saving it all, every bit of longing and need, for each other. We laugh, saying those desk clerks better give us a room on a deserted floor. He was going to head down to Florida, to warm weather and beaches, though he prefers the mountains to the sea, like me. I wasn't going to get involved again, at all, for a long, long time. CC fascinates me the way broken-not-bent people do. I recognize myself in him, I think. He inspires my bones. He sings to my wild. In the hours we spent in the cool, grey light of our motel room he shared such intimate pieces of himself. He was open, unguarded in a way T had never quite been, not in the five years of our relationship. CC told me he was nearly illiterate when he went to prison. He taught himself how to read with Lee Iacocca's autobiography, the only book he had, pouring over it again and again. When he got out a couple years later he bought shelffulls of books, whole rooms full. He said he shipped them all home to his mother for safekeeping when he left LA for Hawaii, but he doesn't know what happened to them. He told me spent years in Hollywood, trying to be an actor. It surprised me a bit at first but now I can see it. There's a certain vanity to CC, and a charisma, too. He takes care of himself - drinking wheat grass juice. working his body out hard - the way people who know they're beautiful do. He told me he's half-Cherokee and half-Polish. He has the high cheekbones and bold brow of a Native American. The strong nose, too, and I can see an echo of his heritage in the shape of his eyes, though they are a muted green rather than brown. He told me when he was about five or six his father took him and his three brothers to K-Mart, where he set them loose, instructing them to go play. Instead, CC quietly followed him, watching from a hidden spot as his dad picked up a set of golf clubs and tried to return them for cash. When the cashier refused, he walked out of the store with them. CC says his dad was a con man. He told me about the women he's loved and the trouble he's made, about his brothers and his mom and how alcoholism runs rampant through his family, like it does in mine. The more CC talked, the more I liked him. He's like a great literary character, I kept thinking, he really is Dean Moriarty in On the Road. I want to write his story - or perhaps I want him to help write mine. I set off in hours for two weeks travels with him, from Nashville to Memphis to Clarksdale, Mississippi, to New Orleans, to Florence, Alabama and back up to Nashville. I've packed more lingerie than I knew I had and stuffed beside the corsets and nighties are fleece jackets and hiking boots, because we like to get outside almost as much as we like to stay in bed. Almost. Along the way we'll be hitting up juke joints and dive bars, blues clubs and honky tonks, as I ferret out the songs of the south for a magazine assignment. I don't know what to expect. I don't know how it will all go down. Maybe we'll end up in Honduras. Maybe he'll teach me the guitar. Maybe we'll part ways and never speak again but always smile when we think of each other. Oh, I love that. I'm so grateful life has the ability to surprise me yet. I should be asleep. It's nearly three in the morning and I leave for Nashville at six. But I'm a night person - my usual bedtime is 2 a.m. or later - and I'm completely amped, anyway. My brain is whirling and swirling like a carnival ride and if I had my own theme music right now it would be very loud calliope, like the kind you hear on a Merry-Go-Round, only sped up about a million times.

A little less than six years ago I met T in Nashville. It was during a press trip, exactly like the one I'm leaving for in a few hours. Until tonight I hadn't been thinking about what this might do to me emotionally, being in the place where we began, where we danced and drank and fucked, not for a moment suspecting that it would change our lives. Hell, I was halfway living with someone else when I met T. Had been for a long time, though we were a couple at that point only in theory. I never told T that. I'm no innocent. Haven't been for a long time. But I started to get anxious tonight, and pretty soon I was wondering if this trip was going to put me right over the edge. I've been a mess for the past month. I'm not sure anyone knows exactly how close I've been to breaking down. I guess I don't really, either. I've been having bouts of real panic and despair, mostly late at night, when I'm alone. When I feel like I'm the last bit of flesh and bone left on the planet. Like only ghosts surround me anymore. The ghost of my brother. The ghosts of my parents, the way they used to be when they didn't hurt so bad in pretty much every way possible. The ghost of T, too. Thing is, I'm starting to come around to the realization that T's abandonment - really, there's no other way to put it when someone who's pledged to spend the rest of his life with you leaves you with barely a word to care for your failing parents alone and disappears, never to be heard from again - so, yes, T's abandonment (and God, does that word make me feel like a loser) isn't the issue. Or, it's less of it than I believed. It's everything else: Gunnar's death, and my parents decline and my friends all leaving this town. Turning 50, too. The fear that I just might never really amount to much. That I'll never fall in love again. I actually think I'm getting over him. Because I'm sick to death of missing him, and I wonder how much of it is me just torturing myself, anyway. Maybe I haven't completely let go because holding on feels so good in the very worst way. My self-esteem is lower than its ever been in my life. Do I think about him because I feel like I deserve to be punished? Or because I need to build the whole thing up in my mind to justify staying in a relationship that nearly erased me? Or simply because, for better or worse, I loved him more than I've ever loved anyone in my life? I've been thinking about something a friend of mine recently wrote me. She was in an abusive relationship throughout her 20s; it took her most of her 30s to heal from it. "Remember, you are free," she wrote to me. "You have YOUR LIFE." Tonight, as I was packing for Nashville, I started trying on clothes. They were things - dresses, pants - that I haven't been able to wear in years, because I gained so much weight when I was with T. (As much as it hurts and embarrasses me to say it, I have a feeling that's part of why he left. That and because it's no fun living with someone trying, and failing, to fight her way out of depression.) These clothes, almost all of them, they hang baggy on me now, enough so that I won't be able to wear them. I've got muscles where I never did before and more energy, even with the fear and sadness I fight every day, than I have...maybe ever. I've got the kind of energy that can climb mountains. Which is exactly what I'm going to do. I haven't forgotten. I just haven't been mouthing off about it as much. Because I have MY life. MINE. And not only can I climb mountains if I want to, I can go on a press trip and not feel guilty about it. not fret about making it back to the room in time for a phone call. And during that press trip - say this one to Nashville - I can wear short, short skirts and show off my long, long legs and go honky tonkin' in my damn cowboy boots. I can drink and dance with anyone I want to, or no one. I can wear some of the drawerfulls of lingerie I have for myself...or for someone I haven't yet met. I can live. Or. Or maybe it's all just bullshit and bravado - which I've been accused of more than once - and I'm simply settling in to my loss. Maybe this is it. What if there isn't more? What if this is who I am now? Someone more than a little broken? Either way, look out Nashville. Here I come. I'm getting stronger. At least physically. Emotionally...well, hell. If every day isn't a battle, it's a skirmish. But my body is changing. I feel it in the way I move, with an ease and pleasure I haven't experienced in years, since I stopped walking regularly. That almost daily, two mile stomp lost to depression and then inertia after I moved in with T. He hated me out in Knoxville at night, alone. But I'd long loved walking under the stars, did it in the quiet of my parents' neighborhood before I moved down south. Sometimes 10, 11 o'clock, I'd venture out, just me and the moon and the sound of the trees ticking in the breeze. The whole world felt like a secret then, whispered just to me.

But Knoxville's concrete didn't have any mysteries - at least none I cared to solve - and the walking fell away. I still don't walk at night, though now there is no one to tsk-tsk at me over its risks. To do so might remind me too much of T, of all the ways I frustrated and disappointed him, and besides, I don't need to - my training at Victory with Steve is returning fitness to me. I recently hiked five miles of local Appalachian forest, the trail taking me alongside mossy, chuckling streams and through glens where ancient mountain laurel loomed overhead, twining together, dense and fearsome. Graceful snakes slithered here and there, peeking out from under slender ferns, while butterflies gamboled overhead. And not one muscle in my body twinged. Nothing ached that day, or the one after, but my eyes, tender from crying, and fragile heart. On Tuesday I begin a two-week ramble through West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. We'll soon see exactly how much my body has evolved under Steve's guidance. I'll be rock climbing, paddle boarding and zip lining with Adventures on the Gorge in the New River Gorge area of West Virginia, a place I adore, that I've to returned to over and over again. It was where I discovered my love of adventure sports, and where I nearly drowned my first time white water rafting, when I was swept out of and then under the boat in a Class V rapid on the New River. Since that day my response to any body of water bigger than than a swimming pool has ranged from mild unease to outright terror, depending on its tranquility. I honestly have no idea how I'm going to cope on the two-day paddle we're taking down the Gauley River, the New's angrier, more brutal sister. One of the world's most violent waterways during dam release season, as it is now, the Gauley's been dubbed by river rats the Beast of the East. I am taking this trip because it is no longer only water which frightens me. It's the fear of living out the rest of my life never feeling again the way I did with T. Of never loving again, and being loved. It's the fear of losing my parents, the last of my family. Sometimes I wonder, daring myself to ponder the inconceivable, how long I have left with them. I live with them. What will happen to me when they're gone? How will I endure their loss? How will I survive adding it to the collection of mean little tragedies I'm too quickly amassing? There is only me left to pack up the house, to get it ready to turn over to the bank. When I try to think about doing that alone, my mind skitters to a stop. I think it's to prevent me from going mad. I'm taking this trip because I'm already drowning. I'm taking this trip because there is no one left to save me but me. I'm taking this trip because I believe it will help return a small, precious part of myself I lost, or, more precisely, abandoned these last few years. This trip is what I believe they call in rafting a self-rescue, the first of many I'll attempt. T famously rafted the Gauley once, during his long-ago grad school days. He had a couple posters of the river pinned up in our kitchen in Knoxville. We had the opportunity to tackle it together a few years ago, when two spots opened up on a rafting trip while we were visiting the area. We didn't do it. It would be too exhausting we said, to raft for hours and then drive home to Tennessee. And T told me - as he had told me many times before that day and would tell me many times after - that he worried about me on the Gauley. "It's big water, baby girl," he said. "It's dangerous." I told him that I needed to raft it, that I wanted to get over my fear. But I tucked his concern away inside me, thrilled and touched that he loved me so much he was afraid for my safety, each time we discussed the Gauley growing a bit more at ease with the idea that rafting it was a challenge I shouldn't face - much like skydiving. A few birthdays ago, when we were still in Knoxville, T had given me a certificate to parachute out of a plane as a present. He'd done it once upon a time, and he knew that I wanted to try it, too. When I opened the card holding the certificate he said, "Now, I'm not really comfortable with this. I'm not sure I want you doing it." And again I thrilled to hear the love, the apprehension in his voice. And somehow that skydiving trip never quite materialized. I don't really know what happened to me in those years with T, why my nerve increasingly failed me, why I began to believe myself weak, incapable. The answer isn't as simple as his coddling concern for me, which, though it rankled a bit, also made me feel protected. Cherished. But I am no longer willing to live my life an eroded version of the woman I used to be. In West Virginia, I'll be rafting some of the nastiest white water in the world. In Delaware, I'll be skydiving. And I'll have stepped a bit further down the path leading to Kilimanjaro and Aconcagua. They're still waiting for me, my mountains, quietly, with terrible patience. |

Jill GleesonJill Gleeson is a journalist based in the hills of western Pennsylvania. She is a current contributor to The Pioneer Woman, Country Living, Group Travel Leader, Select Traveler, Going on Faith, Wander With Wonder, Enchanted Living and State College Magazine, where her column, Rebooted, is featured monthly. Other clients have included Email me!

Archives

May 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed