|

We went easy on our trek through the High Atlas. Slowly and carefully. I was climbing with someone who'd never done anything of the sort and it was enormously difficult for them, not the least because they were terrified of heights. I didn’t know that until we were well on the mule path, when we discovered how steep the drop from it was. Maybe we should have asked Ahmed, our guide, to take us back, but I was already gone, blissful and selfish. Stoned on the discovery that I still belong in the mountains. Or maybe it’s more that I belong to them.

The joy that I felt as the land fell away beside the path, opening up the view to the Berber villages thousands of feet below, was undistilled and overwhelming. It was almost impossible to rein myself in - I wanted to feel my heart thrum and my breath hasten and the muscles in my legs grow hard and unyielding as they struggled to carry me onward. I tried to slacken my pace, but I often found myself so far ahead of the others I had to stop and wait for them. I’d stiffen if I sat, so I remained standing, looking at Morocco spilling out beneath me. It was my first time in the mountains since I failed to summit Aconcagua. I don’t know that I can count the slog up Little Malene in Greenland a couple weeks back, as difficult as it was. I never felt immersed in that landscape the way I did in the High Atlas range. We didn’t venture deep into the outback in frozen Greenland, though the climb was harder, with a sharper elevation gain. The ascent in Morocco was initially gradual. The toughest part for anyone with acrophobia, like the other trekker I was with, was the slender path, and the fear of the long fall if you stepped off of it. Maybe I burned through any fear of falling at the beginning of the trek. I think the greatest concern anyone has for me - at least I’ve been told this, often with as much consternation as love - is that I’m reckless. That I take too many chances, don’t consider the consequences. I suppose it’s true; I’ve been trying to live a more careful life. I don’t know that I’m any good at it. Because after Ahmed gleefully scrambled a few feet up what was more a wall and less a hill, returning to earth dusting his hands with a grin, I challenged him to take me up it. He told me it was dangerous, that the path up wasn’t even a mule trail. It was only for mountain goats and mountain guides, specifically those who had grown up in the High Atlas, like him. But I pushed and Ahmed eventually gave in and up we went. I was fine ascending, even as we climbed hand over feet, 10 feet, 20 feet, 30 feet and even higher. I think I was at one point four or five stories up, totally unsecured, with no one belaying me. The precariousness of my situation didn’t hit me until we needed to start moving across the face of the incline. We left the path, which wound higher, and it made me feel every step was insecure. If I’d fallen I would have bounced until I hit the road that was far enough beneath me I’d have been killed, or at least badly broken. It crossed my mind that I could become a very sad and even more stupid cautionary story about a woman who pushed it too far once too often. After I lost my nerve I spent some time sort of shuffling on my ass across the dirt, stone and scrub, until I felt more stable and could stand, a bit wobbly and ever so carefully, again. In another 10 minutes we'd picked our way off the hill, onto the road. We continued on, methodically trekking toward the Tizi Mzzik Pass, 3,000 feet higher and six miles away. I didn’t feel any elevation sickness along the way, although we eventually reached more than 8,000 feet in elevation. I’m not sure if I should be heartened by that, when it was acute mountain sickness that got me booted off Aconcagua. But I am. I haven’t trained, not once, since coming down from Aconcagua in February, but I felt so strong during the trek. The last section was very steep, a merciless switchback that I climbed slowly, but without getting winded. My steps were sure and I worked my walking sticks well, in proper rhythm with my stride, even as we raced against the encroaching darkness to make it off the mountainside before full night fell. It felt right, my being up there, right the way it is when you fall in love, or the perfect song comes on as you’re driving fast down a back road in summertime, the sun bright and the wind soft. It felt, I suppose, like coming home.

8 Comments

Today, just now, my mom was admitted into hospice.

In Pennsylvania, at least when facilitated by and paid through Medicare, you're admitted into hospice when a physician has determined you have six months to live. In my mom's case, this is connected to an advancing case of COPD that now makes it difficult for her to go up and down the stairs without losing her breath. She has other health issues, including an aortic aneurysm that is slowly enlarging and can't be ameliorated through surgery due to her fragile condition. She's had two recent mini-strokes and she's in the early stages of dementia. So, I suppose this new categorization shouldn't have shocked me and my dad. But it did, of course. The nurse who arrived to talk to us about all this asked us a lot of questions about extraordinary measures to save my mom's life and if we've picked a funeral director and whether we want chaplain services. My dad and I numbly mumbled answers (no, we don't want any; no, but we're thinking cremation - it's starting to be a family tradition, after all, since my brother's death - no, we're not at all religious, but boy, it's times like these I wish we were). I found myself hating the nurse, who's name was Becky. Becky should be a cheerleader. Becky should be a capable mom, arranging car pools and swim lessons. Becky shouldn't be the woman who comes to tell you your mom is dying. I've been told that I need to face up now to this fast-approaching loss. It'll make it easier in the end, my friends say. But the truth is I'm already at the very edge of my ability to cope. These last couple of months I've felt so relentlessly hopeless that I'm not certain I can take one more blow right now, one more goddamn tragedy in the endless stream that the past few years have brought. And so I've been willfully, with a streak of pure, perfect stubbornness I inherited from my mom, disregarding this looming eventuality. Breakdown now or breakdown later? Later seems the better answer. I've been afraid for as long as I can remember of being alone. It's the fear at my center, the one that has motivated so much of what I've done in my life. And now here I am at 51, on the precipice of it. Unable to even date, if the truth be known, because my last relationship was so damaging I'm terrified I'll end up with the same type of man. My brother dead, my mom dying. My dad, 85 and walking around with kidney issues and an unhealed broken neck, getting a little bit more frail every day. No family here. No close friends, they've all scattered to the winds like starlings lifting off from a telephone line. No kids. I might as well be adrift in deep space. The future feels as cold and merciless as I imagine it to be. I'm so fucking scared. I'm so scared. And I don't know what to do. I'm less than six weeks away from climbing the tallest mountain in the Western Hemisphere, the thing I've spent the past 18 months directing so much of my energy, except what I've spent trying to care for my mom and dad, toward achieving. Getting to and up that mountain is the goal that's guided me through the the pain. The heartbreak and the loss. It's kept me sane and promised me a future less ordinary. If I give up now I don't know what will happen to me. But going up Aconcagua is a three-week trip. How can I leave my mom and dad for three weeks now? I'm trying so hard to be strong. I'm squirreled away in my room, writing, because it's the safest place I have. But I've got to stop crying and go hug my dad. After that, I don't know. I started taking an antidepressant today. Wellbutrin, to be specific - a low dose, 150 milligrams. It's been a long time coming. I held out after my brother overdosed three years ago, after my father broke his neck and our dog died and my mom started to lose her mind. Held out, too, when T left almost exactly a year ago. Held out even when my mother was diagnosed with dementia a couple months ago. I told myself over and over that given what I'd been through, was going though, I was doing okay. Anyone in my position would be sad, right? Anyone would struggle. This isn't illness; this is a natural response to a series of vile little gut punches, the kind that life seems to gleefully dole out every once in awhile. I'm okay.

But the thing is, I'm not. I'm not okay. I'm in a dangerous place, a place I've been before, long ago. I have the scars to prove it on the inside of my wrists. Long, vertical ones, the kind you have when you meant it. I've lost the ability to concentrate. I can't focus. Writing - pulling the words out, making something beautiful with them, the thing that's kept me mostly sane this past year - has become nearly impossible. I've slid downhill in the past few months, inexorably, but so slowly at first I didn't notice. I cry all the time now. I do have a few hours occasionally, maybe a couple days or a week if I'm lucky, when I feel a little less pain and fear, when I might actually experience little chunks of happiness. But then I tumble down that well, falling with what seems like no end. I lose hope. I start thinking it would be such wonderful relief to stop this monstrous hurt. I start thinking I want an end like my brother's...just drifting away, peacefully. I think about it, but I don't do it. Instead, I bear down. I push into the hurt until it abates. And then I pick myself up and I go on. But I'm so tired. I can't live this way anymore. And so I messaged my doctor and asked him to write me a script for Wellbutrin. I've been on it before; I know it's about the only antidepressant with no sexual side effects. Hell, even at my lowest there is no way now I'm going to take a med that lessens my ability to experience pleasure, or lowers my interest in having it. That really would send me over the edge. So, Wellbutrin it is. Hello, old friend. It's been awhile, hasn't it? At one point, after I was hospitalized a little more than 15 years ago, I was on Wellbutrin. Seroquel, an anti-psychotic, too. And Depokote, a mood stabilizer, and Celexa, for anxiety, I think. The maximum dosages of all them. I was no longer a menace to society, fucking 21-year-olds and snorting Ecstasy and taking off for Philadelphia with a guy I barely knew to a house I'd never been with nothing but chaos on my mind. Instead, I slept 12 hours a day. I never got sad. I never felt happy. I was stable, doing fine, only occasionally wondering what had become of the woman I once was. I'd been declawed, made safe by swallowing sanity in a bottle. But it felt like just about everything I'd been - good, bad, all of it in between - was lost along the way. After a few years I went off the meds. I was with a partner, living in a beautiful old house in a small town, far removed from havoc and the desire to create it. Without any warning my girl parts turned traitor, demanding that I have children, and fast, before it was too late. So I went off the pills, those bright little bits of stability, all of them, under my psychiatrist's supervision. I stepped down slowly, by lowering the dosages of each med one by one, until I was clean. It took months, unbearable months, when I was so sick I could barely move from the couch. Low-grade migraines that never ended, nausea, exhaustion, dizziness, all day, every day - it was akin, I imagine, to what chemotherapy patients endure. I never got pregnant, but I stayed off the meds. And I was okay. For better than 15 years I was simply Jill: Mercurial yes, difficult but not dangerous, with a shiny spirit that drew people to me. I still sought the edge, but never went over it. I began building a career, discovered that I have an ability to write that people will pay for, and found that I could satiate my need for thrills with sky diving and volcano boarding and the like - less dangerous pursuits then bad boys with big drugs and fast cars and malleable morals. And then I fell hard for T, the man I believed was him, the great love of my life. I'd walked away from the woman who'd been diagnosed as possibly bipolar, but definitely afflicted with Borderline Personality Disorder. I was no longer ill. Not me. And now here I am, back on medication. Does it mean I'm sick again, this little dose of Wellbutrin? Or does it mean I'm well enough to know I need help, a bit of a bump, to set things right again? I thought it would feel like defeat as I slid the first tablet onto my tongue today. But it felt a lot more like relief. I might not be okay, not really, but I think I will be soon. I've been writing a long time about facing fear, about how it cracks open wide your life, and - to paraphrase Leonard Cohen - lets the light in. But I've just discovered it's one thing to face a fear of drowning by whitewater rafting, or of heights by paragliding off a mountain. It's another thing entirely to face a fear that you will not be strong enough to take care of your family when they need you most.

Almost a year ago exactly my father fractured his C1 and C2 vertebrae in a fall. He could have - should have, really - died. But he survived and after hours in our local hospital was transferred by ambulance 90 miles to a medical center with specialists more capable of handling his injury. While I was with him in the ER, T stayed with my mother. She's not really able anymore to spend much time alone. She's got emphysema, is on oxygen 24/7, is in almost constant pain from a distintegrating spine and is beginning to show signs of what I'm afraid is dementia. Once, not long after my brother's death, she was so confused that my father and I had to show her a photo of Gunnar and gently explain to her that her son was never coming home. "He died, Mom," I told her. "He's gone." I held her as she sobbed, thinking there was really not any way that I was going to survive the moment. It hurt too much. You always hear tell about how life is cruel, but until then I didn't understand just gleefully cruel it could be. The night my dad broke his neck my uncle and cousin came to stay with my mother, so T could be with me. We followed behind the ambulance bearing my father, the stars shining down on us with a brillance that only seems possible on the very coldest rural Pennsylvania nights. After Dad was tucked in to the ICU we checked into a motel. I remember I was afraid to go to sleep, terrified the phone would ring and a voice on the other end would tell me my father was dead. We were there three nights, the whole while my aunt and uncle watching over my mom at their house. Finally my father was stable enough to be transferred to a rehab facility in our town, where he stayed for two weeks. But I'd spent a lot of the time he was recovering in ICU numb with fear that I was going to lose him. The rest I'd pondered what I would have done without T. How could I have coped if I'd been without his quiet, steadfast support? What if, after spending all day at Dad's bedside in ICU, I would have had to go back to that motel and crawl into that cold bed, alone? I used to believe I would have broken apart. Maybe I would have. But I'm no longer the woman I once was. The pain of losing T - and my ability to negotiate that pain, as unlovely as the process has been - has honed me. I think it has sharpened my abilities to bear trauma and stress. If it doesn't kill you it makes you stronger. Eventually, that is, after it's first torn you apart, left you bloodied in a ditch by the side of the road. But if you rise up out of that place, the seams where you've stitched yourself together are more solid than you would have believed possible. Three days ago my father went to see his doctor. He wasn't feeling well. Before he could make it in he nearly collapsed in the parking lot. A creatinine blood test revealed he was in kidney failure. I took Dad to the ER, the same ER I'd taken him almost a year ago, after his fall, and waited four or five hours while they ran more tests. Although the ER physician believed his issues were only caused by dehydration, they admitted him. I was forced to leave mom alone. T, of course, is long gone, a memory I'm willing to become more faded, dull, like a Poloroid picture that never quite developed. My mother did fine. I did, too, on my own, taking care of my father. They discovered the next day that both of my Dad's kidneys were blocked by stones, which he's suffered from his whole life. I get them, too. They scheduled him for surgery, to implant stents to drain his kidneys and restore their function. Sometime that day, while Mom and I were visiting Dad in the hospital, our pug dog, Lola, injured herself. When we came home she was having trouble standing on her back legs. I spent yesterday getting Lola to the vet and Mom and me to the hospital, picking up Lola and taking her and my mother back home, making dinner and finally going back alone to the hospital tonight to spend time with my dad. It was stressful. It was exhausting. Mom and I got into a couple of arguments. I need to have so much more patience. Because she's scared, too, just like me. But it looks like Dad is going to be fine, though I just heard they're keeping him another night. We're hopeful Lola will mend, too. My Dad and I have had our issues, our blowups. But last night I was able to sit with him for a spell, reading aloud to him as the hospital quieted around us. I'll never forget it, that time. I'm grateful for it. I'm grateful, too, that I was able to handle everything, all of it, on my own. Not perfectly, or gracefully, or with as much good humor or equanimity as I would like. I want to do better. Unfortunately, I know I'll have the chance to try. But there is comfort in knowing that I didn't fail my parents. In knowing that I'm stronger than I once was - and less strong than I will someday be. I can't make this poetic. I can't make this beautiful. I probably can't even make this especially well-written. I'm so tired. It's a quarter after 11 on a Friday night. I've been crying pretty hard for a while now. The kind of crying that I can't really see through, that clogs my nose and makes my head hurt. The kind of crying that feels like it burns. Like the tears are so hot they scald the skin.

I guess I'm bottoming out. It's nowhere I haven't been but it's someplace I never wanted to return. It's been a long time since I felt this kind of isolation and pain - since back in the bad old days, back when anybody who knew me well probably wondered if I was going to make it. Would I see 25? Would I see 30? Would it be an overdose, a suicide, murdered by a lover? There was a time when I was a Class V tornado tearing through the lives of those around me, though I was as treacherous to myself as anyone else. Almost. I haven't been that girl, wild and reckless, driven nearly mad by an emotional pain that I could never name, in a decade, almost two. I'm still moody, probably always will be. I have a terrible temper. An Irish temper, actually. I've been named a spitfire only recently, and once upon a time, back when we met in Nashville, T called me "a handful." It wasn't so very long ago that a man in a bar took one admiring, appraising look at me and dubbed me "dangerous." It didn't displease me, exactly, though it was in front of a lover who ended our relationship soon after. I intimidated him, he told me. I've been told I glow and shine and pull people to me, almost like T pulled me to my feet and on to the dance floor without even asking that first night in Nashville. Those are good things. But like my brother, my poor lost brother, there is a price I pay for this bit of allure and it's the dark little speckle on my soul I carry, like a burn mark, maybe, or a cold spot. It's smaller than it's ever been. But it's still there and I'm feeling it more acutely than I have in years. I think I know what's going on. I think I know why I'm struggling so much, have been, for a couple of weeks. It's the comedown I always get when I return after a long run of travel - and this time I was out on the road, with just a few days home here and there, for almost two months. It's the goddamn holidays, too, which I dread this year almost with the intensity I dreaded writing my brother's eulogy. It's wrapping up my 60 page book proposal, as well, and the postpartum crash that comes inevitably after the conclusion of a big project. And it's the election, of course. Because I'm afraid, really afraid, of what's already happening to this country. I'm not easily frightened, at least not of men in dark alleys and low-lit parking lots. I've always walked where I wanted, when I wanted. I'm 5'9", I'm strong, and I move with assurance. It's protected me so far - or perhaps it's just been thanks to the same kind of fortune that safeguards drunks and small children - but I'm wondering if that blissful carelessness must now end. A friend of mine, a lover off and on through the years, messaged me the other night, concerned for my safety in the light of recent attacks on women. He was conflicted, but in the end advised me to get a gun and learn how to use it. But it's not really the possibility of physical violence that scares me. It's the vulnerability of my parents and me. We are so alone. I'm 50 years old, now partner-less, and doing my best to take care for them without any help at all, while working very long hours as an independent journalist. I make little money doing this, though I'm good at it. I am starting to see a little daylight; I've been getting better paying assignments and more of them. I hope to be making a decent living eventually from journalism, but in the meantime I supplement my income by working part-time seasonally in Penn State's Office of Admissions. My parents have outlived most of their savings, which was gutted by the market crash after 9/11. My dad has an unhealed fracture of his C1 and C2 vertebrae. My mother has COPD and is in severe pain from back issues; the two conditions have nearly rendered her bedridden. I take medication for various ailments, including diabetes, although I'm working hard to get in shape with the hope I can greatly alleviate these conditions. I see a therapist weekly. I believe if it weren't for her I might have been hospitalized. It's been a horrific few years. If it weren't for Medicare and Medicaid my parents and I wouldn't have health care. If it weren't for Social Security we might not have a place to live. I wonder, if the new administration has its way, how we're going to survive. And in the midst of all of this, two weeks ago, my therapist left the practice I use, one of the few that takes my insurance. She wasn't happy there, and told me during our last session that she had only stayed as long as she did so she could continue to counsel me. Laura understood me, saw me clearly and without judgment in a way few people ever have. I told her everything. Everything. I would walk into her office, terrified and sobbing, and she'd had me a tissue, patch up my psyche and send me on my way. Me thinking I just might be able to make until the next appointment. The last time I saw her she told that I give her faith in humanity. She actually said that. Faith in humanity. How do you respond to something like that? I just thanked her. Told her she might have saved my life. My new therapist is different. She wants me to fill out some kind of worksheet. Say affirming things to myself in the mirror. Write a goodbye letter to T, for God's sake. She says I'm in denial about the end of our relationship. I have trouble with that. The last thing in the world I want to be is some sad woman pining for a man who doesn't deserve her. It is possible to be in denial when I know that my life will be far, far better without him? I know we could never be together again. I don't know that I even still love him. I'm...processing. It would be so much goddamn easier to process if I could just be in another relationship. Although, I suppose the processing would stop, and that's the problem, isn't it? I hate being alone. I'm as terrible at it as I am terrified by it. I love love. And sex. And romance. I've been married once, engaged three times, and lived with I don't know how many men. But I'm trying to change my life, to heal that dark little speckle inside of me. And as Laura once said to me, "If you want a different result, why don't you try to do things differently?" And so that's what I'm doing, but the result is nights like this. Nights when I want to give up, but somehow manage to hold on, believing in the morning I'll feel just a little bit better. I'm getting stronger. At least physically. Emotionally...well, hell. If every day isn't a battle, it's a skirmish. But my body is changing. I feel it in the way I move, with an ease and pleasure I haven't experienced in years, since I stopped walking regularly. That almost daily, two mile stomp lost to depression and then inertia after I moved in with T. He hated me out in Knoxville at night, alone. But I'd long loved walking under the stars, did it in the quiet of my parents' neighborhood before I moved down south. Sometimes 10, 11 o'clock, I'd venture out, just me and the moon and the sound of the trees ticking in the breeze. The whole world felt like a secret then, whispered just to me.

But Knoxville's concrete didn't have any mysteries - at least none I cared to solve - and the walking fell away. I still don't walk at night, though now there is no one to tsk-tsk at me over its risks. To do so might remind me too much of T, of all the ways I frustrated and disappointed him, and besides, I don't need to - my training at Victory with Steve is returning fitness to me. I recently hiked five miles of local Appalachian forest, the trail taking me alongside mossy, chuckling streams and through glens where ancient mountain laurel loomed overhead, twining together, dense and fearsome. Graceful snakes slithered here and there, peeking out from under slender ferns, while butterflies gamboled overhead. And not one muscle in my body twinged. Nothing ached that day, or the one after, but my eyes, tender from crying, and fragile heart. On Tuesday I begin a two-week ramble through West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. We'll soon see exactly how much my body has evolved under Steve's guidance. I'll be rock climbing, paddle boarding and zip lining with Adventures on the Gorge in the New River Gorge area of West Virginia, a place I adore, that I've to returned to over and over again. It was where I discovered my love of adventure sports, and where I nearly drowned my first time white water rafting, when I was swept out of and then under the boat in a Class V rapid on the New River. Since that day my response to any body of water bigger than than a swimming pool has ranged from mild unease to outright terror, depending on its tranquility. I honestly have no idea how I'm going to cope on the two-day paddle we're taking down the Gauley River, the New's angrier, more brutal sister. One of the world's most violent waterways during dam release season, as it is now, the Gauley's been dubbed by river rats the Beast of the East. I am taking this trip because it is no longer only water which frightens me. It's the fear of living out the rest of my life never feeling again the way I did with T. Of never loving again, and being loved. It's the fear of losing my parents, the last of my family. Sometimes I wonder, daring myself to ponder the inconceivable, how long I have left with them. I live with them. What will happen to me when they're gone? How will I endure their loss? How will I survive adding it to the collection of mean little tragedies I'm too quickly amassing? There is only me left to pack up the house, to get it ready to turn over to the bank. When I try to think about doing that alone, my mind skitters to a stop. I think it's to prevent me from going mad. I'm taking this trip because I'm already drowning. I'm taking this trip because there is no one left to save me but me. I'm taking this trip because I believe it will help return a small, precious part of myself I lost, or, more precisely, abandoned these last few years. This trip is what I believe they call in rafting a self-rescue, the first of many I'll attempt. T famously rafted the Gauley once, during his long-ago grad school days. He had a couple posters of the river pinned up in our kitchen in Knoxville. We had the opportunity to tackle it together a few years ago, when two spots opened up on a rafting trip while we were visiting the area. We didn't do it. It would be too exhausting we said, to raft for hours and then drive home to Tennessee. And T told me - as he had told me many times before that day and would tell me many times after - that he worried about me on the Gauley. "It's big water, baby girl," he said. "It's dangerous." I told him that I needed to raft it, that I wanted to get over my fear. But I tucked his concern away inside me, thrilled and touched that he loved me so much he was afraid for my safety, each time we discussed the Gauley growing a bit more at ease with the idea that rafting it was a challenge I shouldn't face - much like skydiving. A few birthdays ago, when we were still in Knoxville, T had given me a certificate to parachute out of a plane as a present. He'd done it once upon a time, and he knew that I wanted to try it, too. When I opened the card holding the certificate he said, "Now, I'm not really comfortable with this. I'm not sure I want you doing it." And again I thrilled to hear the love, the apprehension in his voice. And somehow that skydiving trip never quite materialized. I don't really know what happened to me in those years with T, why my nerve increasingly failed me, why I began to believe myself weak, incapable. The answer isn't as simple as his coddling concern for me, which, though it rankled a bit, also made me feel protected. Cherished. But I am no longer willing to live my life an eroded version of the woman I used to be. In West Virginia, I'll be rafting some of the nastiest white water in the world. In Delaware, I'll be skydiving. And I'll have stepped a bit further down the path leading to Kilimanjaro and Aconcagua. They're still waiting for me, my mountains, quietly, with terrible patience. Last week, the day after my 50th birthday, I went to see my friend Shaie speak at the BuxMont Unitarian Universalist church in Warrington, outside of Philly. I occasionally attend services when I'm traveling, like the achingly beautiful mass given in Irish I witnessed on St. Paddy's Day in my beloved Dingle, Ireland a couple years back. But the habit is more about honoring and exploring the local culture than anything else. I'm not at all religious, though I guess you could call me spiritual. I'm uncertain of what comes next after this life, but I believe, or at least I very much want to, that something does. I've lost too many people I loved too much in the past few years to long consider any other possibility.

Though I attended the Unitarian service simply to support my friend, the sermon nonetheless worked it's way into me. Shaie, who is currently seeking her master's degree in divinity at Vanderbilt, spoke in her soft, sweet voice about the times in life, as she described, "that feel simultaneously empty and full, containing both endings and beginnings, moving the experience of life from what is known to what is new." She titled her sermon "The Blank Rune," after the stone in the ancient set of divinatory symbols that represents contact with true destiny, which may hold our highest good and yet brings to the surface our deepest fears. This space between that Shaie spoke of, where all is uncertain, filled with equal parts panic and potential, is where I live now. My past life, with a love I thought would last forever, with a younger brother I thought would live forever - Gunnar always seemed simply too vital, too big and filled with energy to ever die - and with healthy parents who could tend to themselves, is over. My new life, with its quest to ascend Kilimanjaro and Aconcagua next year, has barely begun. There is little I know with any sureness. Instead, there are only questions. Will I be able to make my body, mind and spirit strong enough to climb Kili, let alone the nearly 23,000-foot behemoth that is Aconcagua? Will I find the support from sponsors I need to make these trips happen? Will I have it within me to write a book about it all? Will I have it within me to care for my mom and dad with the compassion and diligence they deserve? Will I find great love again? And will I finally, finally make of my life something I can be proud? I have underachieved my entire adulthood, veering close to big, traditional success upon occasion, like the time I was one of a half-dozen women under consideration for the sidekick position on mega-star Mancow's syndicated radio show. But I never quite made it, always distracted by fallout from my chaotic life, or the next novelty to catch my easily unfocused attention. Often a man. Often a man broken and unworthy. The drug addict. The rage-aholic. The commitment-phobe incapable of intimacy. I used to joke that, given my choices in previous companions, my next lover would be a serial killer. It's not a joke I make anymore. I'm leaving these loves, and whatever emptiness within them that called to the hole in my soul, forever behind. No matter if its a place of healing, the space between is uncomfortable - it often hurts like hell, actually. It's terrifying to have no real idea what the future holds, only plans and intentions, dreams and desires. Living in the space between requires faith, a faith I find myself struggling to capture. It's like stepping off a precipice, trusting you will float rather than fall. But trust is really the only option, because when you start to fret about the future, to worry it, like rosary beads between the alabaster fingertips of an ancient cleric, you stop living. Trepidation sets in. Dread. And before you know it, you are immobilized. You become one of those people beaten by life, unsatisfied, unhappy, but incapable of reaching for better. More than anything I fear this surrender. So I'm trying to trust in the process, as Shaie suggested in her lovely sermon. To breath deeply and exist in the still, small moments - as yet rare and all the more precious for that paucity - when I am able to let go of doubt. I've set my goals and I'm working toward them. I will work toward them with more diligence, passion and focus than I've ever worked toward anything in my life. That's really all I can do, anyway. Work hard. Trust big. Trust that there is beauty and love and adventure and joy, too - real joy - ahead. Trust that all this pain and fear will one day dissipate, leaving just a distant, disquieting recollection, an ashy smudge of a memory of the time when I thought I just might not make it. I turned 50 years old an hour and 15 minutes ago and since that time I've been writing and deleting, writing and deleting. I want to pen something profound and beautiful, something wise, with humor and grit, to mark this occasion. The thing is...I don't feel that way. I don't feel beautiful or wise. My 40s seem to have taken my sense of humor with them and the only grit I've got at this point is the bit of mascara still left in the corner of my eye after a day spent crying. I was supposed to be on a beach in Cuba right now, drinking mojitos and making love in the sand.

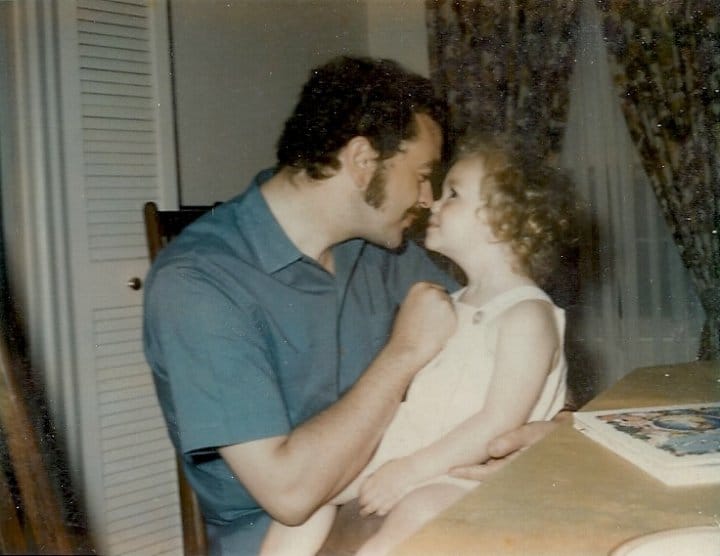

I feel like I was knocked on the head and have woken up in a life that isn't my own. Surely I can't be 50 years old, with an epically busted heart, living with my parents as I try to take care of them - and not very capably at that - while attempting to jump start a career in a field that is disappearing faster than the polar ice caps? To quote David Byrne, "How did I get here?" I suppose a more helpful question might actually be "How do I get out of here?" How do I get back to myself, the woman I was years ago, when life held measures of joy and promise? Ascending Kili and Aconcagua - and the physical, emotional, mental, even spiritual work that I have to do in preparation for those climbs - is half of the answer. The other half is easier to achieve, though probably more complicated. I've got to fake it 'til I make it. Are you familiar with the concept? Basically, you act the part of who and what you want to become, faithfully and with gusto, until you actually become that person. I think it's about using intent and action and maybe even a bit of visualization to make manifest your dreams and desires. And it works. It really does. I faked it 'til I made it years ago, back before I started traveling and doing things that really alarm my mother, like fording rain-swollen Wyoming rivers on horseback with 6'5" cowboys named Bob and investigating gay leather clubs in Amsterdam. In those days I knew what I wanted - a big life - and what I wanted to become - fearless. I acted that part, pretending to be a big, bold adventurer until it seemed that was what I'd become. For a while. And then I fell harder and more deeply in love than I think I've ever been in life. And my big world started to get smaller. I started to get smaller. Because sometimes big, bold, world-stomping women aren't what men want. Even when that's half the reason why they fell in love with you in the first place. And when those men who you've changed your life for - hell, tried for years and years to change your very essence for - when they turn around and leave anyway? They leave behind a wraith, a pale shadow, someone with only a vague recollection of who they once were and what happiness feels like. I don't remember what it's like not to be sad, not to be scared. So I'm going to try to fake it 'til I make it. I'm going to pretend, as best as I can, to have strength and purpose, energy and even joy. I'm going to imagine that I'm still the woman in this picture up there, which was taken just a couple years ago, by a good friend and just for the sheer hell of it. That woman in the photo - confident, spirited, even gleeful...I want her back. I'm afraid it's too late, that at 50 I'm too old. But I'm going to pretend I'm not. I have a tendency toward impulsivity. Something bright and shiny and thrilling and BIG pops into my head and I think "Ooooh! Good idea! Let's GO, baby!" Leave my family and friends and everything I know to move down to Tennessee and in with a guy who has TWICE before cracked my heart open like an uncooked egg by breaking up with me the moment real commitment or true intimacy became involved? "Ooooh! Good idea! Let's GO, baby!"

We all know how that turned out. Though I can say now, six weeks out from when T walked - no, ran is a much more accurate word - six weeks out from when T ran out of my life I don't regret that move to Tennessee. I regret plenty of other things about our relationship, but not that. Because if you're going to be impulsive about anything, it might as well be love that at its best was so true blue if it had a color it would be the shade of the sky over the desert after a storm. No matter how big the hurt it eventually brings. Of course, you're catching me at a good moment. Ask me how I feel about it when I'm sobbing at the dining room table before my stricken parents in the middle of supper and I might not be quite so perky about the whole thing. I still cry. A lot. Not every day, but close. I still, if you want to know the truth, cannot quite believe he's gone. At best, I miss him right down to my bones. At worst, I find it ridiculous that I'm expected to continue on without him. At very, very worst, like last night, I'm seized fully with a terror of the future looming in front of me, sinister and ugly, like a dark shadow in a desolate alley. Of the alien aloneness of it. T left. My brother is dead. When my parents are gone, I'm it. The last woman standing. Anyway, as you might have guessed, I did not agonize over the decision to climb two of the Seven Summits in '17. I began with the idea to tackle Kilimanjaro next summer. I remember thinking something along the lines of "The last time T broke my heart I moved to Ireland for five months. This is the last, last time he will break my heart. So what in the hell do I do now?" And there came the image of Kilimanjaro, unbidden, blasting its way into my brainpan. Almost immediately I decided to blog about the experiences I would have as I trained to climb the mountain, thinking maybe it might not only do me some good, but also a few other people. People like me, who had lost so much they were in danger of losing themselves, too. Then a few days later I heard that a lot of people climb Killi, about 25,000 annually, so shortly after that I decided to up the ante and add Aconcagua to my list. Only about 3,000 a year try it, maybe because it's known in South America as "The Mountain of Death." And then I got a web designer and a trainer and a photographer and went public with the plan and...here we are. The whole process, from "Ooooh, good idea! Let's GO, baby!" to now took three weeks. I want to think there is something magical in that - the speed, the ease, with which it all came together. But now it's finally hit me, exactly what I've done. And I'm so scared. Not precisely because of the climbs...it's more the failure that could come with attempting them. Suppose no one reads my blog? Suppose I can't find any sponsors? Suppose I just can't do it? Because who do I think I'm kidding? I'm just a frightened, desperate mess. I'm not brave or a warrior. I'm not even a jogger. How in the hell am I going to get this nearly 50-year-old, out-of-shape body up two of the tallest mountains in the world? I really have no idea, other than to work harder than I ever have before and listen to the guys at Victory Sports and Fitness. I had my fitness assessment at Victory last week. I was nervous, really nervous, because I pictured getting asked to do a pull-up, failing miserably, and everybody in the gym laughing at me, which is pretty much what happened in 5th grade. But instead Rob, Victory's energetic and charming owner, simply evaluated my posture, flexibility and range of motion. He discovered that my left calf is slightly less developed than my right - and assured me we'll get that squared away. He found that both my big toes only bend about half as far as they should. We'll deal with that, too, because I need my feet in good working order for Summit Day on Aconcagua, a 12-hour trek to the top. My scapulas, however, are in great shape - strong enough, Rob assured me, to bear the pressure without a shoulder dislocation if I take a tumble during the ascent and catch myself with my hands. That's as long as I don't fall 65 feet into a crevasse, like two Americans did on Aconcagua a few years ago on New Year's Eve. I'm not telling my parents about that. A couple days after the evaluation I had my first session with my trainer, Steve Jury. Steve is about my age, with a big mustache and kind eyes. I like him very much. I also trust him to know what I need to do to get up those mountains because a couple months ago Steve did just that on Kili. The day I met him he showed me pictures of Africa he'd taken from the top of the world. In a few he's perched in front that epic, endless landscape, the place where man began, smiling so wide you'd think it was the best day of his life. Maybe it was. Our first session surprised me. I don't know what I expected - Steve hurling medicine balls at my stomach while screaming at me to "Feel the burn," maybe. Instead, mostly what I did, along with a little cardio and some serious ankle and big toe stretching, was breathe. Flat on my back at first, later with arms held over head, then legs extended out and finally while on all fours, I breathed. From my diaphragm, with lips pursed, pulling my belly in with every exhale. It seemed easy enough. Too easy. Breathing? "Baby steps to big steps," Steve said. I liked that. Steve also said "Suffer now and summit later," which I liked even more. It sounded tough, like something I can chant to myself when I want to quit during a workout or practice climb. I understood the concept more clearly by that evening. My core, from my pelvis up to my breasts, had begun to ache with a dull, consistent pain that I hadn't felt the likes of in a long time. It's the pain, I suppose, of beginning. The pain of hope, too, perhaps. Because hope hurts just as much as it soothes, doesn't it? That's the hell of the thing. Baby steps to big steps. |

Jill GleesonJill Gleeson is a journalist based in the hills of western Pennsylvania. She is a current contributor to The Pioneer Woman, Country Living, Group Travel Leader, Select Traveler, Going on Faith, Wander With Wonder, Enchanted Living and State College Magazine, where her column, Rebooted, is featured monthly. Other clients have included Email me!

Archives

May 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed